A survival guide for life insurance and bancassurance managers: metrics and underlying valuation assumptions (part 2/2)

02 July 2021

The first part of this article started exploring some of the critical value drivers of life insurance companies and the pitfalls of several underlying valuation assumptions. In particular, it looks at Annual Premium Equivalent (APE), Value of New Business (VNB) and New Business Strain (NBS). We briefly mentioned that the VNB is the VIF minus the NBS.

We looked at the building blocks of the New Business Strain (NBS), which is the initial cost of acquiring new insurance contracts.

- We showed that the interests of the customers, the distributors, and the insurance company managers might be far from aligned.

- We also showed that managers must understand their products, their customers, and the distribution network. It is a necessary (but not sufficient) condition to grow the business in a way where expected profits at sale's time will indeed materialize years later. In particular, it requires significant efforts and initiatives for the right products to be sold to the right customers. It is the only way all three parties can benefit: customers get the products they need and can afford, distributors get a fair remuneration, and the insurance company will realize the future profits expected at sale's time.

Moving on and as previously mentioned, we need two components to compute the Value of New Business (VNB): the New Business Strain (NBS), which we covered in the first part of this article, and the Value In Force (VIF) discussed below.

NB: as a reminder to my actuarial or accounting colleagues, this article might appear simplistic or even approximative. It aims at providing a watered-down but helpful understanding for managers. It is not meant to prepare for an actuarial exam.

Exploring the drivers of the Value in Force (VIF)

The VIF is meant to reflect the expected future profits generated from the in-force business, i.e. the insurance contracts held on its books by the insurer. Whether we have a new or existing contract, it has a VIF.

The VIF typically depends on:

- The expected premium(s) to be paid and the nature and shape of these premiums over time: Regular Premium, Single-Premium, etc

- The expected customer lapse rate: will customers keep paying their premium? How many will stop? Depending on the terms of the contract and when the customer stops paying, the consequences are not the same, and the contract is not necessarily void.

- The costs allocated to serving these contracts (called "maintenance expenses" ), i.e. a proportion of the company costs deemed attached to running the existing business (by opposition to acquisition expenses which would be the portion of the costs allocated to bringing in additional customers, contracts or top-ups on existing contracts).

- The fees charged to customers, such as the annual management charge, i.e. a percentage charged on customers' assets held in the contract.

- The discount rate used when calculating the present value of future revenues and costs.

- The return on the assets invested, i.e. if the assets invested on behalf of the customers grow, so will the insurer's revenues via the annual management charge (as defined above, it is a percentage applied to these assets).

- The trail commission to brokers (if any): this would be the part of the commission that is not paid upfront at the time of the sale but later on during the contract's life.

Understanding the drivers of the Value in Force (VIF)

One should now better understand how easy it is for managers to be misguided with so many parameters involved in calculating the profitability of insurance contracts.

Let's illustrate this point by continuing with the example we used in the first part of the article. We touched on the fact that distributors have an incentive to sell life insurance with longer terms and higher premiums that customers may need or can afford. This phenomenon subsequently means that insurance managers -particularly in countries such as the UAE or South-East Asia- must watch the customer lapse rate, i.e. the proportion of customers who stop paying their premiums. Specifically, they must compare the assumed lapse rate at the contract's start versus the real number as it materializes over time.

The lapse rate is an interesting parameter, and its impact on profitability depends on the specific nature and set-up of the insurance contract. For example, a customer lapsing will stop paying its premium, meaning fewer revenues than planned for the insurer. It can also mean fewer costs if the contract is subsequently invalidated and customers can no longer claim (e.g. the death benefits). In this case, everything the customers paid to date is 'for nothing' , and they got no benefits (assuming they did not already lodge a claim). In the first case, one would note that the insurance company and its shareholders lose out, whereas in the second case, customers lose out. The only party who always wins is the distributor, as his commission (or the bulk thereof) is paid upfront at the time of the sale.

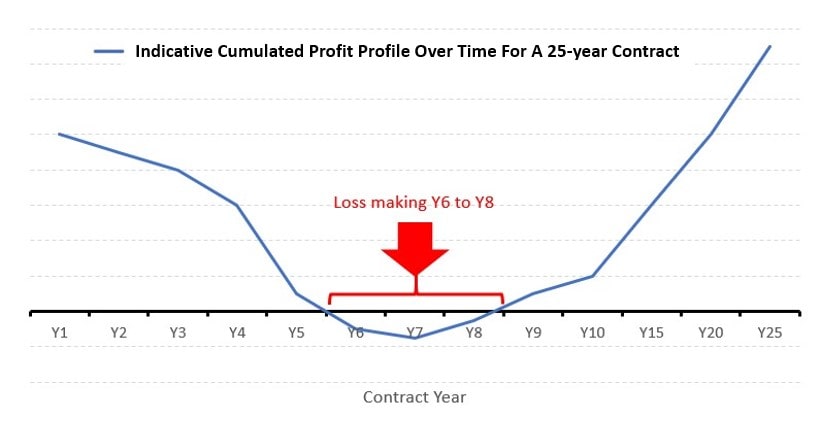

Our prior example, a Regular Premium 25-year contract product, has a profit profile which is loss-making from year 6 to year 8. Meaning if customers stop paying their premiums in these years, the insurance company makes a loss.

It also turns out that this contract features heavy penalties if customers stop paying their premiums in the first 5 years of the contract. You might wonder why this is the case, and it is worth explaining. The initial commission paid to the brokers needs to come from somewhere. And the only source of fresh money is the monthly premiums paid by the customers. So, only part of these premiums is initially invested to generate returns, and the rest goes towards the brokers' commission. In other words, the insurance company pays the commission upfront at the time of the sale and 'reimburses itself' from the premiums of the early years. This means that far from 100% of the customers' premiums are invested in the initial years, and it takes a few years for these invested funds to grow back to the cumulative sum of premiums already paid. In other words, the penalty for stopping premium paying too early is just reconciling the reality of the funds invested and available (once the brokers' commission has been paid first) with what the customers think they have invested (when adding up the total premiums paid to date).

Summarizing what we have understood so far:

- Brokers have a financial interest (higher commission) in customers buying a life insurance plan with a higher premium and longer duration that they might need and/or could afford.

- Customers will lose money if they stop paying their premiums in the first 5 years of the contract. They will be faced with penalties to get their money back, and these penalties are just there to pay for the brokers' commission.

- Per the chart above, the insurer will make a loss if customers stop paying their premiums in years 6, 7 or 8.

- From year 9 onwards, both the insurer and the customers get something out of this contract: the insurer should make a profit, and customers should see their investment money grow (while also having a death benefit). In any case, the brokers got their commissions at the time of the sale.

One can see that this product does what it is supposed to do if customers pay their premiums over the long term (which is what they bought). The issue arises if they were sold a product not suitable to their needs or did not foresee that they would not want or could pay a premium for decades.

This is not the end of the story for the insurance managers, and it gets worse from there. Indeed, at the end of the initial 5-year penalty period, the brokers will call back their customers and convince them to stop paying the premiums because "there is now a much better life insurance contract elsewhere" . The brokers do not say that they will now get brand new sales commissions from these alternative insurance companies. In the Middle East or South-East Asian markets, we typically see brokers churning their customer books to capture a fresh sales commission every x years (with x depending on the contract terms). In this case, this situation creates a problem for the initial life insurance company. As shown in the chart above, customers will lapse in year 6 or so, creating a real loss on a 25-year contract that was expected to be profitable at sale's time and was reported as such in the company books.

This is the real-life scenario I described earlier with an insurance manager not watching lapse rate indicators or unaware of the typical business dynamics. He will do victory laps for a few years based on paper profits before exhibiting real losses some years later.

As we can see above, many drivers impact the value and profitability of an insurance book. A well-advised insurance manager can definitely act on some of them (e.g. lapse rate, customer fees, commission levels and structure, etc.). However, managers are more limited when it comes to discount rates or long-term expected returns, albeit there are still some levers to pull. For example, in France, managers can try to steer customers away from a guaranteed fund called 'fond en Euro' and into Unit-Linked funds ('Unites de compte' ). In this case, there is a liability attached to the guarantee, coupled with the challenge of delivering a semi-decent return by investing in safe bonds in a low-interest-rate environment as we had since 2008. It is easier and less risky to let customers take the entire investment risk by placing their assets in Unit-Linked funds and simply collecting a fee as a percentage of these assets.

Once again, we see the inherent conflict in the asset management space between shareholders and clients whereby the balance of risk/return may shift back and force depending on the market and/or regulatory conditions. Shareholders and managers can limit or steer customers' choices while customers can be smart by looking at the best deals in a competitive market. Of course, this assumes that customers can actually understand the products in-depth (something quasi-impossible) or be advised by competent and really independent financial advisors (a rare species: search on youtube for 'John Oliver retirement plans' . It is worth watching).

New Business Margin

It is the VNB divided by the APE. In other words, it is a sort of Profit to Sales ratio and gives a sense of the expected profitability margin. Readers will note that it comes with all sorts of caveats starting with the assumptions contained in the VIF and the embedded assumptions in the APE that Single Premium insurance contracts are 10-year contracts (even if it is not the case. Please refer to the first part of the article).

The Internal Rate of Return (IRR) and the Payback period

As explained above, when calculating the VIF, one has to use a discount rate. The internal rate of return (IRR) for a policy is the discount rate for which the sum of discounted profits and New Business Strain (NBS) equals zero. There are some subtleties whereby one has to use post-tax VIF and pre-tax NBS, but this is beyond our purpose. The Payback period is the length of time it takes for the new business to return sufficient profit to pay back the initial cost of writing this business. It is easier to think in terms of the payback period rather than IRR.

The important points here are:

- The payback period and IRR are inversely related. The higher the IRR, the smaller the payback period. The lower the IRR, the longer the payback period.

- An insurance company will want a higher IRR (i.e. a faster payback period). In fact, there is usually a minimum threshold required for product approval (e.g. 15%).

- The IRR is an expected number subject to all the VIF and NBS calculation assumptions. So it is aspirational at the time of sales, and the insurance firm will have to wait a few years to see facts confirm or infirm the expectations.

VNB versus IRR and payback

One easy way to understand how these metrics are helpful is to think like this:

- The VNB measures the size of the expected profits, whereas ...

- ... the Payback period / IRR measures when these profits are expected to materialize (i.e. how far in the future)

Embedded Value (EV)

The Embedded Value (EV) of a book of an insurance business is broadly made up of a majority of VIF and a minority of Net Asset Value (NAV). The EV comes in various flavours beyond the purpose of this article, e.g., European EV (EEV) or Market Consistent EV (MCEV).

The Net Asset Value represents the assets held within the business over those held to meet future payments to policyholders and future costs/expense payments.

For a given book of contracts, the VIF will go down year after year. And therefore, so will the EV assuming the NAV remains broadly constant. This is because -all other things being equal- when time moves forward one year, the first year of the VIF (called the 'in force surplus') becomes the cash surplus. It is no longer held in the back book of contracts but is becoming 'real' cash. It can be used to run the company (e.g. paying for various items) or distributed to shareholders as dividends if there is enough above and beyond capital requirements.

Wrap-up

The life insurance industry -particularly its investment products- is a complex business to understand and value accurately. It is both intangible and a very long term business (e.g. 10, 20, 30 years). These characteristics make it challenging to reflect the value of contracts that run decades in the future in today's financial statements.

In addition, life insurance managers tend to have a poor understanding of the metrics used and the underlying assumptions. As such, it is easy to mismanage such business and confuse paper profits with real gains.

In my opinion, the key is the relationship with the customers. It is often an intermediated sale whereby the distributor is the middle man and does not necessarily have an incentive aligned with the best interests of both the customers and the insurers. However, the process of disintermediating such sales is not easy because of the complexity of the products and the subsequent regulatory oversight (one needs to be a qualified financial advisor, although said qualification varies vastly by country).

To disintermediate the sales process, an insurance company must challenge the status quo and engage in a virtuous circle. Indeed, it has to make products easy to understand for customers. In turn, this means getting rid of all the hidden fees and various subtleties placed in contracts to compensate for the poor practices and excessive costs built in the industry. Therefore, this implies seriously trimming cost structures by focusing on improving processes and efficiency. However, with a legacy of very old contracts which still need to be managed, this exercise is not easy. There is a therefore a good chance for Insuretech firms to compete effectively by starting from a clean slate. We will see what the future holds. For the moment, I personally have seen Insuretech mostly focusing on sleek mobile-phone apps and interfaces but the underlying insurance contracts are still the same.