A survival guide for life insurance and bancassurance managers: metrics and underlying valuation assumptions (part 1/2)

28 June 2021

If you work in life insurance and wonder what NBS, VNB, or VIF mean but never dared to ask, you came to the right place.

This two-part article will explain some of the critical value drivers of life insurance companies and the pitfalls of several underlying valuation assumptions. It will show managers which indicators to monitor to make sure that expected profits materialize.

I consistently observed that many managers lacked an understanding of the business dynamic, the relevant metrics, and the value of existing or new life insurance contracts. Yet, at the same time, individuals do not dare to ask for fear of appearing incompetent. Sadly, this compounds the problem over the years, as the more senior in the business, the larger the fear to ask for basic information. As a result, I have seen the situation where the MD of an insurance business does a victory lap touting his glorious paper profits (solely due -of course- to his extraordinary business skills), only to face significant actual losses a few years later (hint: in emerging countries, watch the 'lapse rate' assumption vs reality!).

The life insurance industry -particularly its investment products- presents specific characteristics making it prone to intended or inadvertent misrepresentation of the truth. It is:

- Intangible, i.e. an obligation for an insurer to pay a monetary amount to the insured customer if an event (covered in the contract) happens in the future

- A very long term business, i.e. 10, 30 or more years, making it challenging to reflect in today's financial statements the value of contracts that run decades in the future.

Even with the best intentions, it isn't easy to accurately reflect the value of an insurance contract at the time of the sale and throughout its life. For example, it depends on the probabilities of a covered event (e.g. death) happening within the duration of the contract, or it depends on whether or not the customer will stop paying his premium. To make things worse, it also depends on the economic environment in 10 or 20 years: what will interest rates be in 10 years? What will the return of the stock market be over the next 15 years? etc.

There are methods and regulatory frameworks to help businesses value their insurance contracts books consistently. Yet, with so many hypotheses along the way, this is bound to be incorrect. In addition, managers have a vested interest (i.e. $$ annual bonus) in showing shareholders the value arising today from an intangible future twenty years out. Sadly, with assumptions only becoming facts in twenty years, one can guess which direction said assumptions are possibly 'massaged'.

First, let me warn my actuarial friends that this article might appear simplistic or even approximative. However, I hope they will agree that if everyone in life insurance had this minimum level of understanding, their life would be more straightforward, and they would not be asked to approve products with only a faint chance of ever being profitable.

The most overused metric: Annual Premium Equivalent (APE)

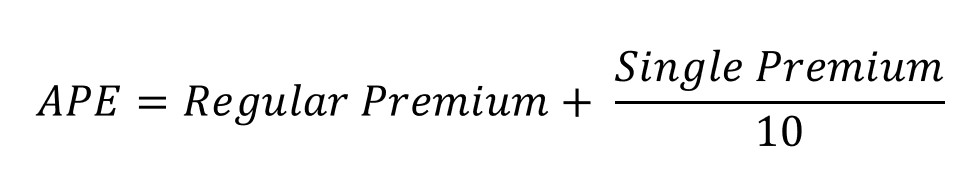

Let's start with APE. It allows a degree of comparison between the sale of policies with two different types of premium: those policies where the premium paid is an annual Regular Premium (RP), and those where the premium paid is a one-off initial Single Premium (SP). In other words, it is a measure of sales volume measured in currency terms, e.g. £, $, EUR, etc.

The attentive reader might wonder why a Single Premium is converted into an annual premium by dividing by 10 and not by 5 or 20? Well, this only works under the assumption of an average life insurance policy lasting 10 years. Therefore, taking 10% of a single premium annualises the single lump-sum payment received over the 10 years the policy would be in effect.

As one can see, even the most basic measure of currency unit sales volume (i.e. the APE) has a significant underlying assumption about the duration of a Single Premium life insurance contract sold. Thus, if the life insurance contract is anything but 10 years, this formula does not reflect the reality. Yet, it is widely used in the UK. This is not a good start.

'New Business' in Life insurance: VNB, VIF and NBS

Defining 'New Business' in Life insurance

'New Business' in a given calendar year includes:

- New insurance policies

- Additional Single Premium contributions made on existing policies

- Increase in Regular Premiums made on existing policies

- New entrants to Corporate insurance schemes (i.e. the Life insurance that you may elect to choose as part of the benefits package offered by your company)

Where the fun starts: valuing 'New Business' in Life Insurance

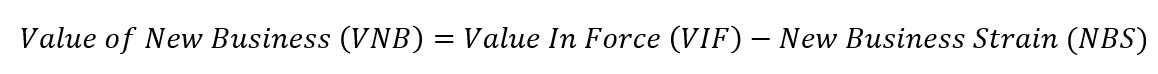

Valuing new life insurance business means calculating the Value of New Business (VNB), also referred to as the New Business Value (NBV). To do this, we estimate the expected profit from this new business, i.e. calculating the so-called Value In Force (VIF). We then subtract the initial cost of acquiring this business, called the New Business Strain (NBS).

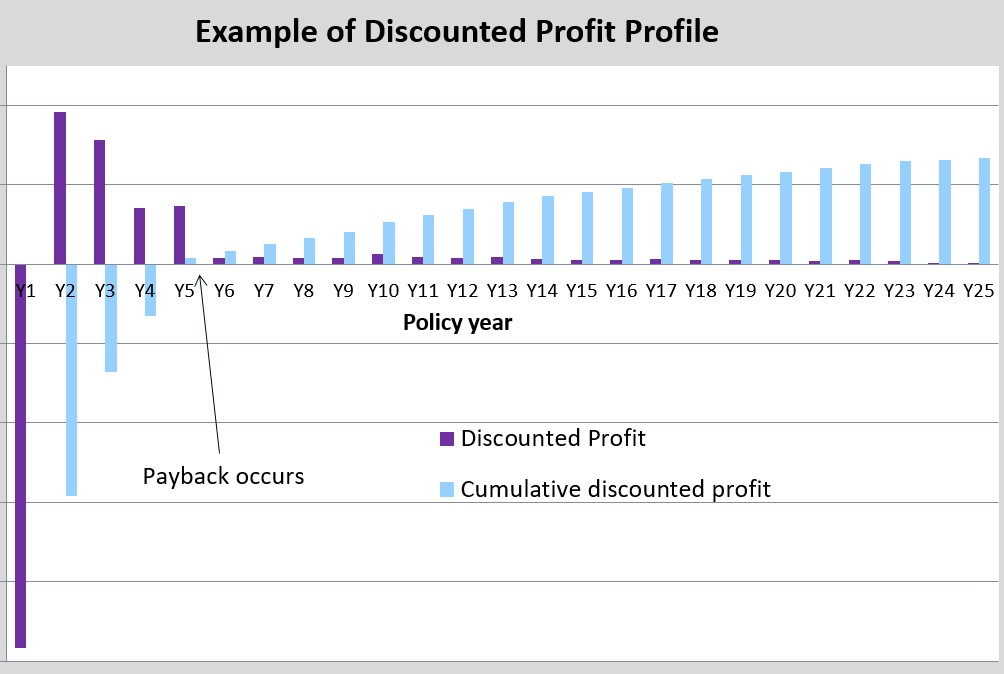

A) To calculate the Value in Force (VIF), we need to value expected profit streams that will come in over the duration of the insurance contract, e.g. over the next 10, 15, 20 or 30 years. These expected profit streams are calculated as expected revenues (such as the premiums paid by customers) minus the expected matching costs.

A simple example of these costs is the cost of the customer service centre. In ten years, customers paying their annual premium (= revenue for the insurer) also expect someone to man the customer service phone (= cost for the insurer). The important point here is to use the Present Value of these future profits, i.e. the Present Value of revenues and costs. Indeed, in the case of expected premiums and other than the first one(s), they will be paid -by definition- in the future. Receiving $1,000 today is not the same as receiving $1,000 in 15 years. So, we need to count all the premiums in the same money, i.e., today's money. In other words, we discount them back to the current year. We also use the same discounting approach for expected future costs. This gets us to the Present Value of the expected future profits (profits = revenues - costs). By discounting all expected future profits to the present time, we obtain the expected Value In Force (VIF) from this new life insurance business.

B) The initial cost of acquiring the business is the New Business Strain (NBS).

For example, it can be the initial commission paid to the broker or the agent that closed the sale with the customer.

Click here for a larger image (pop-up window)

The New Business Strain (NBS)

Let's start with the initial cost of acquiring the business, i.e. the New Business Strain. It will help articulate key concepts that will be useful later.

The initial cost of writing the new business is made up of:

- Acquisition expenses, i.e. the part of the overall cost of running the business that can reasonably be allocated to acquiring new business. For example, a marketing campaign to push the sales of a specific insurance plan would be an acquisition cost. There is, of course, a degree of arbitrary decision from management in terms of deciding which costs are deemed acquisition costs.

- Up-front commissions paid to the brokers, the sales force or the distributor.

- Capital required to hold for reserves.

- And, possibly, capital required to hold for solvency.

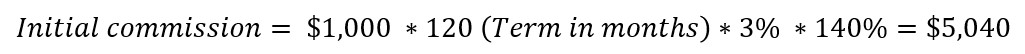

Let us look more closely at the up-front commissions and use the example of a regular premium product sold by a broker in the Middle East with a $1,000 monthly premium (to be paid by the client), a 10-year term (the term of the contract during which the client has to keep paying the monthly premium), a 3% commission factor, and a 40% distributor 'override' (a further incentive to the broker).

This structure would be typical in the UAE and works out as:

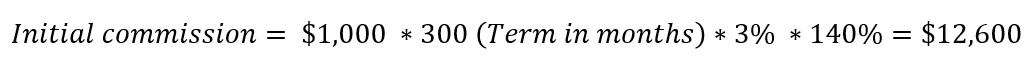

Now, let's make this a 25-year policy:

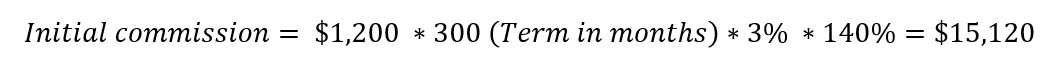

...and increase the monthly premium to $1,200:

The dynamic should now be clear. An independent insurance broker is incentivized to sell:

- Products from the insurance company that rewards the most generously (e.g. here, a 3% commission factor and a 40% override), and...

- ... within the product range of a given insurance company, products with the longest possible term and the highest possible monthly premium (when structured as the Regular Premium contract above).

The reader should now realize that there is an obvious misalignment between the financial interest of the broker, the interest of the customer (do they need so many years of cover? can they afford to pay a high premium for so many years? ) and even the interest of the insurance company. Indeed, as we shall see later, an insurance company thinking it has acquired a customer who will pay $1,200 for the next 25 years will be in for a nasty surprise if the customer stops paying his premium in 3, 5 or 7 years. The expected profit booked at the time of the sale is simply not going to materialize and will need to be adjusted in the books a few years later.

The astute reader or manager might consider adding a claw-back condition to the broker to incentivise him to sell contract terms more suited to the client's real needs. Sadly, as in the wealth management business, power lies with the party owning the relationship with the customers, i.e. the broker, the financial adviser or the distributor in general. If the commission terms become less favourable with a given insurance company, the broker will shift to selling the products of a more generous and accomodating competitor.

This, therefore, presents a significant challenge for an insurance manager. First, he has to see and recognize the issue, and I can tell you first-hand that this is not always the case. Second, and assuming the issue is understood, it brings the question of how to best deal with this complex problem. Sadly, some might be tempted by a career-focused quick action plan: increase incentives to brokers, subsequently make lots of sales (knowing that the expected profit will not materialize but is going to be recorded anyway for the first few years), do the rounds with headhunters to market themselves as amazing business leaders (it needs to be done in 2 to 4 years max), and upgrade job in said 2 to 4 years, i.e. before the books must be corrected to reflect the true value (or loss!) of what has been sold. Repeat.

Allow me to support the above example with real numbers from the Middle East dating a few years back. Take a specific Regular Premium product that shall remained unnamed for this article. The average contract term sold in the Middle East for this product was 18.5 years. Yet, only 33% of customers were paying their premium after 5 years, and only 26% of customers were paying their premium after 8 years!

In summary of this section, sustainably and consistently reducing new business strain is a challenging task. First, it requires analytics and insights product by product, region by region, distributor by distributor. Second, it requires acting both on the acquisition expenses and the initial commission payments.

The former implies looking at efficiency gains across the organization, e.g. can we onboard customers and/or new contracts more effectively? Could we consider new distribution channels, i.e. digital? Assuming alternative distribution channels have been explored, one can then tackle the commission structure of the distribution network. Some options can be considered. For example, make a portion of the commission aligned with long-term persistency experience, provide analytics and insights to brokers as a way to enlarge the relationship and the negotiation space beyond the commission (e.g. can the insurer build an analytics team and help brokers sell more effectively to the right customers?), improve subscription forms to ensure that customers realize the long-term nature of their commitment, etc.

Wrap-up

Now that we explored at high-level the initial costs of acquiring new life insurance business, the second part of this article will look at the drivers of the Value In Force (VIF), i.e. the expected profit streams over the duration of the insurance contract.

We will see that when these assumptions are incorrect, paper profits can quickly turn into real losses. We will also look at other metrics and keywords such as New Business Margin, Internal Rate of Return (IRR), or Embedded Value (EV).